You’ve Been Here Before: Ul de Rico’s Chromatic Eden

I. Invocation / Lure

I don’t recall exactly the circumstances of how I got there, but I do recall the feeling that I didn’t belong in Felix’s house. We weren’t close schoolmates, he was maybe a grade or two ahead of me. He ran in different circles. I do remember the smell of his home: musty carpet, something vaguely metallic, ghost of something fried lingering in the air, the tang of adolescence in his dim bedroom. The blinds twisted shut, walls plastered with prog rock posters. Not that I was adverse to prog, but I had recently sworn fealty to New Wave and I knew it was heresy to gaze upon them. He played Rush’s Hemispheres on repeat that afternoon. Side B… over and over while the summer breeze breathed warm air in through the open window and gently rattled the blinds. It wasn’t necessarily bad music, but it felt like homework set to 7/8 time. He let it play end over end—same three songs a dozen times (maybe a hundred, I don’t know). He closed his eyes and was lost in another nine and a half minutes of “La Villa Strangiato.”

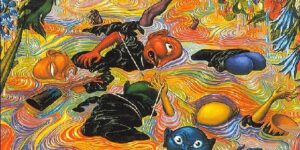

From my spot where I sat on the floor, I felt awkward. Looking around for a distraction now that the conversation had lapsed, I saw the children’s book The Rainbow Goblins lying open on his shelf, mid-spread. I reached for it slowly the way one might approach a mouse trap and brushed the seeds from the page. Maybe it was the music (or secondhand effect from what Felix had smoked), but what I saw didn’t feel like an illustration. It was too deep, too wet, too alive. Every leaf seemed to sweat. The goblins gleamed like oil slicks with teeth. The page wasn’t flat; it had depth, like you could fall into it and be devoured by the vines. With Hemispheres swirling in the background, Geddy Lee’s voice climbing impossible ladders, it all fused. I left that day with a grudging affection for Rush and an awe for Ul de Rico.

II. Some books open doors. The Rainbow Goblins opened a world that watched you back.

Ulderico Conte Gropplero di Troppenburg sounds less like a name and more like an incantation you’d find etched into the crumbling stucco of a decaying Venetian bell tower. To some, he was a minor Italian illustrator of books; to others, a maximalist in prismatic myth and celestial awe. Born in Italy, trained in Munich, he emerged not from the illustration world so much as tunneled up through the mossy underlayer beneath it. He painted with rich, layered, glistening oils not to depict a thing, but to become it. His canvases were not flat. They were wet and alive, like something still in the process of blooming… or feeding.

The Rainbow Goblins isn’t just a children’s book; it’s a warning myth painted in light. The story is simple, archetypal: Seven goblins, each obsessed with a different color, travel through the land trying to steal the hues from rainbows. They are devoured, in the end, by nature itself. But the real story is in the texture of his brushwork, the violence hidden in beauty, the way the colors seem to retreat from the viewer, protected by flora that curls and constricts like defensive muscle. De Rico’s world was not “fantasy” in the usual sense. It wasn’t whimsical or cute. It glowed from within, as if lit by something sacred and endangered. And though he painted for children’s books, his goblins weren’t cartoon villains; they were seductive parasites. His valleys weren’t safe havens; they were sentient, protective, and merciless.

He only published two children’s books under his own name: The Rainbow Goblins (1978) and The White Goblin (1996). Each reads like a fable for a world on the brink—stories about color, greed, and nature’s judgment. But the words are barely necessary. The paintings tell the real tale. Look long enough, and you begin to hear them.

III. The Sound of Color

Before The Rainbow Goblins, de Rico conjured myth on a Wagnerian scale. In The Ring of the Nibelung (1977), he illustrated the operatic cycle not with bombast but with surreal tenderness. Gods and giants, dwarves and dragons loom, softened by mist and myth. Mountains curve with improbable grace. Rivers gleam like veins under translucent skin. Even Valhalla, rendered in his oils, feels like a fragile mirage. Glorious, but already crumbling.

His vision echoed beyond the page. Masayoshi Takanaka’s The Rainbow Goblins (1981) is a jazz fusion homage to the book that doesn’t merely interpret, but extends. Takanaka’s guitar drips light. The album plays like sunlight refracting through jungle mist. Synths flutter like wings. Every track sounds like a different ecosystem waking up. It isn’t a soundtrack; it’s a companion world.

Then came the counter-spell. In 2017, Primus released The Desaturating Seven, a concept album inspired directly by The Rainbow Goblins. But where Takanaka glided, Les Claypool gnawed. The album is a darker echo, full of chromatic hunger and sinister playfulness. Goblin voices croak through pitch-shifted growls. The rhythms skitter like nervous insects. The cover art mimics de Rico’s vertical spreads with towering, surreal, and dangerous imagery. It sounds like the moment just before the goblins are devoured, when the colors begin to fight back.

De Rico didn’t just illustrate stories. He seeded worlds and imaginations. And others heard the resonance.

IV. Cinematic Fractures & Cult Survival

De Rico’s vision was not confined to the page. His work extended into film, most notably in The NeverEnding Story (1984), where he contributed to the design of the world of Fantasia. The skies, the aurora-lit expanses, the sweeping, otherworldly terrains bear his chromatic fingerprint. His sensibility is there in the bones of the film: in the shimmer of the Ivory Tower, in the weight of Gmork’s shadow. Likewise, his designs filtered into Flash Gordon (1980), where pulp futurism meets baroque fantasy. His fingerprints are faint, but they haunt the aesthetic of the frames.

Ul de Rico is the artists’ artist. A cult figure, whispered influence. His books circulate like contraband through rare book circles, passed hand to hand like talismans. Collectors know. Artists nod in quiet reverence. The goblins live on not because of marketing, but because readers remember. Because painters saw those pages and heard a call.

V. Coda / Benediction

Fast forward to 2025, I walk out to the lending library we put up in the side yard by the sidewalk, across from the elementary school. I re-stock it with more books. I survey the spines of books others left behind. I see it there, a well-worn copy of The Rainbow Goblins leans against some other donations.

Somewhere beneath the surface of this weary world, the color waits, not dead, not dormant, but dreaming. In the roots. In the riverbeds. In that liminal moment before the storm breaks and the sky fractures into impossible hue.

The rainbow isn’t gone. It’s just hiding. Waiting for the worthy.

Go back. Find it. Touch the moss. Smell the sky.

Be First to Comment